Team Enablement through the Spirit of Play - Optimising Adult Learning

Author: Jose Francis Llenado (RPsy, MA.Org Psy, BS Psy)

Dr Victoria Verlezza (Belfer Center, Women InPower)

Peer Reviewed - Carolyn Burr, M.Lead, Grad Dip Couns, B.A.,

The Power of Play

Play enables unlocking team enablement in purpose-driven organisations. In organisational contexts where performance pressures are high, play is often dismissed as trivial or counterproductive. Research increasingly demonstrates that play can be a strategic enabler of resilience and innovation.

Neuroscience studies show that play activates dopaminergic reward pathways, which enhances motivation and learning retention, making it a powerful tool for adult learning and professional development (Chang & Plucker, 2023). Similarly, organisational psychology highlights that playful environments reduce burnout and foster stronger interpersonal bonds, which are critical in high-stakes, purpose-driven organisations (Mukerjee & Metiu, 2021).

Moreover, meta-analyses of team training underscores that playful, experiential methods significantly improve team outcomes, including cohesion, adaptability, and collective problem-solving (Klein et al., 2009). In caring organisations that prioritize empathy and collaboration, play becomes a regenerative practice that sustains emotional labor and nurtures creativity (Elsawah, 2025). It is emerging as a serious modality for enabling human-centered leadership and organizational flourishing.

Reframing Play from Distraction to Strategic Tool

Play, at its core, is voluntary, imaginative, and emotionally engaging. When embedded into team culture, it fosters psychological safety by creating low-stakes environments where experimentation is encouraged and mistakes are reframed as learning opportunities (Mukerjee & Metiu, 2021). This psychological safety is a cornerstone of adaptive collaboration, allowing teams to navigate ambiguity and complexity with confidence. Developmental psychology also suggests that play is integral to cognitive flexibility and social learning, reinforcing its role as a strategic tool for adult teams (Lillard, 2015).

Rather than prescribing rigid frameworks, play invites co-creation and shared meaning-making. In organisational design, playful structures mirror the dynamism of real-world challenges, enabling teams to practice adaptive responses in safe, simulated contexts (Elsawah, 2025). This approach democratizes leadership by allowing individuals across hierarchies to step into roles of influence and insight. In this way, play is not a gimmick but a deliberate modality for activating latent leadership potential and fostering distributed agency.

Evidence-Based Impact of Play (in Individuals and Adult Learning)

The evidence base for play spans neuroscience, psychology, and organisational studies. Neuroscientific findings reveal that play activates the brain’s reward systems, enhancing intrinsic motivation and improving retention of new knowledge (Chang & Plucker, 2023). This makes play particularly effective in adult learning contexts, where engagement and memory consolidation are critical. In organisational psychology, playful environments have been linked to higher employee engagement, stronger interpersonal bonds, and reduced stress, all of which contribute to healthier workplace cultures (Fu & Li, 2025).

Design thinking methodologies also rely on playful ideation to unlock convergent and divergent thinking and inclusive problem-solving. By encouraging experimentation and imagination, play enables teams to generate novel solutions and challenge entrenched norms (Resende et al., 2025). In caring organisations, play surfaces untapped leadership potential by creating conditions where individuals feel safe to take risks and share ideas (Chang & Plucker, 2023). Thus, the evidence suggests that play is not only enjoyable but also a multifaceted phenomenon that enhances engagement, innovation, and connection.

Why Care Delivery Organisations Need to Play More

Care delivery organisations, such as those in healthcare, education, and social impact. face unique pressures such as resource constraints and mission-driven complexity. Play offers a regenerative counterbalance by creating space for reflection, renewal, and connection. Research shows that play reduces stress and fosters resilience, enabling teams to shift from reactive firefighting to proactive co-creation (Mukerjee & Metiu, 2021). In emotionally demanding contexts, play provides a safe outlet for processing experiences and sustaining well-being.

Play democratises leadership by allowing all team members to contribute insights and innovations, regardless of formal authority. This distributed agency is particularly valuable in caring organisations, where collaborative problem-solving is essential to mission success (Fu & Li, 2025). By embedding play into organizational culture, leaders can cultivate environments that prioritize empathy, equity, and creativity. In doing so, play becomes not just a source of enjoyment but a strategic mechanism for sustaining purpose-driven work.

The Future of Enablement Is Playful

As workplaces evolve in complexity, traditional approaches to team development are proving insufficient. Play offers a future-ready modality that aligns with the needs of organisations navigating uncertainty and change. Evidence from gamification in adult education demonstrates that playful structures enhance learner engagement and adaptability, preparing teams to thrive in dynamic environments (Elsawah, 2025). Similarly, systematic reviews of creativity in organizational contexts highlight play as a catalyst for innovation and inclusive collaboration (Resende et al., 2025).

When teams play with purpose, they cultivate psychological safety, strengthen relational bonds, and unlock collective intelligence. This makes them not only more effective but also more human and connected. In this sense, play is not a luxury. it is a necessity for organisations that aspire to shape the future with care, creativity, and resilience.

The Inductive Process of Adult learning and Andragogical paradigms

Dole N.D; Ortigas, Perez, (2009) in Hechanova, (2017) suggests that adults learn best when they involve themselves in the experience of learning, rather than become a passive observer. This is the fundamental axiom of adult learning and transformational leadership-from a top-down perspective to a more democratic exchange of ideas. Play optimizes this as it generates a space for genuine meaning making.

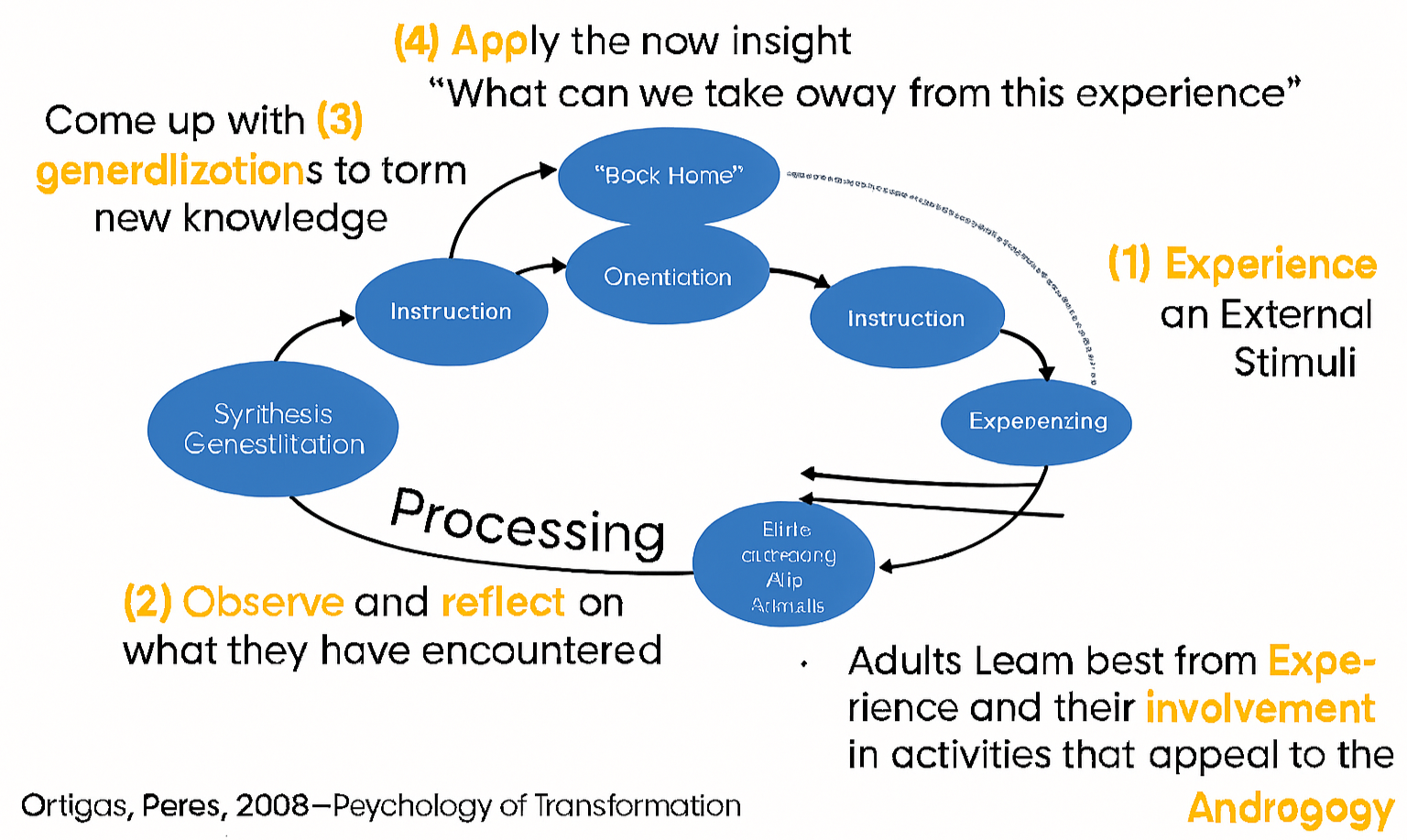

Module designs can either be Inductive (experiential learning) or deductive (framework learning). The former operates from a bottom up learner-centered approach, and the latter from a top down framework approach. In both learning scenarios, facilitators must operate from an andragogical facilitation approach in order to deliver the training needed to maximize outcomes. Most andragogical approaches highlight the importance of outcomes based learning in which learners are facilitated to produce a learning outcome rather than taught how to learn.

A key feature of adult learning is metacognitive and generative learning - reflecting experience through a semi-structured process that draws out meaning and identifies its core components. Deep learning would involve a facilitative process of looking back on an experience in a structured way to make sense of it and figure out what really matters. (i.e. what is this experience telling me). An active process of this examination allows for a regular “update” of the model by which the learner views the experience (Ortigas, 1994; Ortigas Perez, 2008; MacKeracher, 2007, Starkey, Tempest, mcKinlay, 2014)). Learner or coaches role is to facilitate through active learning and development.

Figure 1.0 The Adult Learning Cycle – Psychology of Transformation (Ortigas, 1994; Ortigas Perez, 2008)

Role of Leaders as Facilitators

There is also a critical human development lens through which these learning games and experiential activities should be understood. From a developmental perspective, well-designed games function as structured social laboratories: they create low-risk environments in which individuals can explore trust, identity, power, communication styles, and behavioral patterns without the high stakes typically present in organizational or educational settings. By inviting participants to experiment with ways of thinking, relating, and responding, these experiences support psychological wellness and growth across cognitive, emotional, and social domains. In particular, games can normalize differences, differences in identity, processing speed, comfort with ambiguity, leadership orientation, and emotional expression, while reinforcing the idea that there is no singular “right” way to participate or contribute.

When facilitated intentionally, these experiences actively reinforce psychological safety by redistributing authority, encouraging voice, and making learning visible as a collective, iterative process rather than an individual performance (Hunter & Bailey, 2009). Participants are empowered to navigate multiple identities (professional, cultural, neurocognitive, relational) while practicing skills such as boundary setting, perspective taking, adaptability, and mutual accountability. In this way, games become more than engagement tools; they are developmental interventions that support self-awareness, relational competence, and resilience.

Enabling this type of learning requires essential skills from the coach or trainer, skills generally known as facilitation. Facilitation represents a critical pedagogical practice rooted in inductive, group-centered leadership, designed to enable learning and development rather than control outcomes. Central to effective facilitation is the facilitator’s capacity to recognize and integrate learners’ subjective realities, their lived experiences, identities, emotional states, and ways of meaning-making, with objective instructional goals. This integration allows the facilitator to calibrate pace, structure, and depth of engagement in ways that are responsive to both individual and collective needs.

Beyond shaping group dynamics, facilitators perform a set of distinctive communicative functions that directly support learning and psychological safety (Edmondson, 2018). Active listening attends not only to the content of participant contributions but also to their emotional tone and implicit meaning. Reflective paraphrasing ensures shared understanding while validating individual perspectives. Clarification helps translate complex or abstract ideas into accessible language, and linking connects individual contributions into coherent patterns of collective sense-making. Communicating acceptance of all contributions, regardless of perceived sophistication or relevance, reduces evaluative judgment and reinforces inclusion. Finally, facilitators demonstrate humanness by acknowledging strengths, limitations, uncertainty, and growth as universal aspects of learning and leadership.

Together, these practices underscore the facilitator’s dual responsibility: to guide the group toward its learning objectives while honoring the relational, emotional, and developmental dimensions of human interaction. In game-based and experiential contexts, this dual focus is especially critical, as the quality of facilitation often determines whether an activity merely entertains or truly transforms.

Flattening Hierarchical Structures through Play

Games provide a natural mechanism for flattening hierarchical structures by shifting focus away from titles and positions toward capabilities and contributions. In productivity-focused environments, structured play such as role-switching exercises, improvisational games, or collaborative problem-solving challenges allow individuals to showcase skills without the constraints of formal authority. Research in organizational psychology highlights that these playful contexts accelerate trust-building and interpersonal familiarity, enabling teams to “get to know each other quickly” in ways that traditional introductions or meetings cannot (Mukerjee & Metiu, 2021). By removing the weight of hierarchy, games democratize participation, allowing latent talents to surface and fostering a culture where insight and creativity are valued over positional power.

Raising Awareness of Creativity and Innovation in an AI World

Games also serve as experiential “laboratories” for creativity and innovation, skills that are increasingly indispensable in a market shaped by artificial intelligence. Playful ideation activities such as divergent thinking games, design sprints, or storytelling challenges. These help teams practice generating novel solutions and reframing problems. Neuroscience research shows that play activates reward pathways that enhance divergent thinking and problem-finding (Chang & Plucker, 2023).

In an AI-driven economy, where automation handles routine tasks, human creativity becomes the differentiator. Games raise awareness of this shift by immersing participants in imaginative scenarios that highlight the value of curiosity, adaptability, and innovation. They remind teams that creativity is not a luxury but a survival skill in markets where AI accelerates change and disrupts norms. Play facilitates genuine creativity by introducing spontaneity in a safe space.

Team Enablement Training in Rapidly Changing Workplaces

In workplaces characterized by rapid change and disconnection, games offer a unifying modality for team enablement training. Experiential simulations, cooperative challenges, and gamified learning modules provide safe spaces for practicing adaptability, resilience, and collective problem-solving. Meta-analyses of team training confirm that playful, experiential methods significantly improve cohesion and adaptability (Klein et al., 2009). By embedding games into enablement programs, organisations create environments where teams can rehearse responses to uncertainty, strengthen relational bonds, and build performance capacity. In this way, play becomes a strategic rehearsal ground for thriving in volatile, disconnected contexts.

The team enablement training series within UntappedME™ is designed to foster interpersonal connection, group cohesion, and team level “outside the box” thinking” by creating an inclusive and safe space to practice adaptive thinking and innovation through the spirit of (role) play across 3 key areas - Trait Detective, Quest Detective and Reflective Detective. This curriculum which has been informed by research and expertise, blends experiential learning, guided reflection, and interactive gameplay.

Returning to Old-School Group Learning

Games also reconnect teams with the “old school” tradition of learning in groups, where collective exploration and shared meaning-making drive deeper understanding. Collective meaning is formed from the spontaneous discovery of outcomes through play (Peterson, 1999) In a sense, games enable the formation of a “meta-game”; ma map of meaning that enables a way to conduct oneself in various domains outside the game space. This can be further highlighted in the process of inductive learning, outlined above, where meaning is formed through lived experience.

Group-based play, through cooperative puzzles, role-play scenarios, or storytelling circles, revives the communal aspects of learning that digital and individualized training often overlook. Developmental psychology underscores that play is integral to social learning and cognitive flexibility (Lillard, 2015), and these benefits extend into adult professional contexts.

By returning to group-based play, organisations tap into the wisdom of collective learning, and subsequently unlock untapped talent through fostering empathy, dialogue, and shared accountability. This approach both strengthens knowledge retention and reinforces the cultural fabric of teams, reminding them that learning is most powerful when it is relational and co-created.

We'd love to know: what are your all time favourite games?

This Article contains cited materials from existing evidence-based sources. All referenced content is cited using APA format. A comprehensive list of references is provided at the base of the article, as well as in text citations is the article sections

The reference listing included in this article were constructed with the assistance of AI, which organized APA formatting based on the meta tagging of the bulleted journal articles and references.

References

Chang, Y., & Plucker, J. A. (2023). Problem finding and divergent thinking: A multivariate meta-analysis. Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts. Advance online publication https://doi.org/10.1037/aca0000570

Elsawah, W. (2025). Exploring the effectiveness of gamification in adult education: A learner-centric qualitative case study in a Dubai training context. Discover Education, 1(2), 100031 https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2666374025000317

Edmondson, A. (2018). The Fearless Organization. Wiley

Fu, X., & Li, Q. (2025). Effectiveness of role-play method: A meta-analysis. International Journal of Instruction, 18(1), 309–324. https://doi.org/10.29333/iji.2025.18117a

Hechanova, M.R., Calleja, M.T., & Villaluz, V.C. (2014). Understanding the Filipino worker and organization. Ateneo Center for Organizational Research and Development, Ateneo de Manila University Press, Loyola Heights, Quezon City, Philippines

Hunter, D., & Bailey, A. (2009). The Art of Facilitation.

Klein, C., DiazGranados, D., Salas, E., Le, H., Burke, C. S., Lyons, R., & Goodwin, G. F. (2009). The effects of team training on team outcomes: A meta-analysis. Journal of Applied Psychology, 94(3), 541–558. ttps://psycnet.apa.org/doiLanding?doi=10.1037%2Fa0013022

Lillard, A. S. (2015). The development of play. In R. M. Lerner (Ed.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science (Vol. 2, pp. 425–460). University of Virginia.

Mukerjee, Jinia & Metiu, Anca. (2021). Play and psychological safety: An ethnography of innovative work. Journal of Product Innovation Management. 39. 10.1111/jpim.12598. retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/publication/354403677_Play_and_psychological_safety_An_ethnography_of_innovative_work

Ortigas, C. D., & Perez, J. P. (2009). Psychology of transformation: The Philippine perspective—Philosophy, theory and practice. Ateneo de Manila University Press.

Peterson, J. B. (1999). Maps of Meaning: The Architecture of Belief. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Resende, L. M., Pontes, J., & de Barros, R. (2025). Exploring creativity and innovation in organizational contexts: A systematic review and bibliometric analysis of key models and emerging opportunities. Journal of Innovation and Knowledge, 10(3), Article 100061.https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S2199853125000617#:~:text=These%20articles%2C%20along%20with%20their,at%20translating%20theory%20into%20practice.

Reyes, J. S., & Reyes, E. C. (2025). Systematic review and meta-analysis: The role of storytelling in enhancing mathematics education. International Journal of Research and Innovation in Social Science, 9(6), 2876–2879 https://ideas.repec.org/a/bcp/journl/v9y2025issue-6p2876-2879.html